The Oil of Gladness

The Oil of Gladness

Isaiah 61:1-3 & St. Matthew 2:19-23

By William Klock

Our Gospel lesson this morning tells us how Jesus came to live and to grow up in the town of Nazareth. St. Matthew tells us:

But when Herod died, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, saying, “Rise, take the child and his mother and go to the land of Israel, for those who sought the child’s life are dead.” And he rose and took the child and his mother and went to the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was reigning over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there, and being warned in a dream he withdrew to the district of Galilee. And he went and lived in a city called Nazareth, so that what was spoken by the prophets might be fulfilled, that he would be called a Nazarene. (Matthew 2:19-23)

The Gospels of Christmastide tell us the Nativity story from St. Matthew’s perspective. They jump around a bit, so we don’t quite get the story in order—the part about the wise men, of course, is saved for tomorrow—for Epiphany. But our Gospel today picks up towards the end of Matthew’s second chapter.

Let’s back up, though, for some context. At the beginning of Chapter 2 the wise men arrive in Jerusalem, following an unusual star—some think it was the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. In those days the planet Jupiter was associated with kings and many people associated Saturn with the Jews. Seeing their conjunction, the wise men—astrologers from the East—concluded that a great king had been born in Israel. They naturally went to Herod, but he knew nothing about it. He sent them on their way, but he was troubled. It’s highly doubtful that Herod would have considered this a serious threat, but he decided to “take care” of any potential problem, just in case. He asked the wise men to stop on their way home to tell him what they had found. When they returned by a different route, Herod decided the safest course of action was to murder all the baby boys in Bethlehem, two years old and younger.

And so Herod’s soldiers marched to nearby Bethlehem. There were probably ten to fifteen little boys two years and younger in the small town. They weren’t hard to find. The recent census probably made it easy. It’s an awful story. How could these men murder innocent children in cold blood? But it’s one we see over and over again in history and even spread across our newspapers today. Families, fathers, mothers, and little children massacred in war and in genocide. It’s happening so frequently in places like Yemen and Iraq and Syria that it’s hard to keep up. And lest we think these awful things only happen in far-away countries, we have our own atrocities here. It makes it easier that so many deny their humanity and that we do it in clean medical facilities, but we murderer our own unborn by the tens of thousands every year in this country and millions more do so around the world. God created us to be his friends and to rule his Creation in his name, but in our rejection of him we have become a cruel and evil race, subjecting each other to unspeakable things—the strong running rough-shod over the weak.

We wonder how Herod could do such a thing, but just remember that this was a man who murdered his own family just make sure he had no rivals. He even murdered his own wife. As he was on his death bed he issued an order that the leading citizens of Jericho be murdered—so that there would be people crying at his funeral. He was an evil and brutal man and the people under his rule suffered for it. When we think of the oppression that the Jewish people lived under in the time of Jesus we usually think of the Romans, but Herod was there too and while the cruelty of the Romans was usually predictable, Herod’s was not—it was often chaotic and arbitrary.

When St. John opens his Gospel by talking about light coming into the darkness, this is the sort of darkness he had in mind. And Jesus was born right in the middle of it. This is what so many people simply couldn’t grasp. They expected the Messiah to come as a great warrior—like King David, but much more glorious and powerful—to drive away the darkness. They expected him to turn the tables. But that’s just it. Turning the tables only means that the oppressed end up becoming the oppressors. God had something much better in mind—something to stop the whole cycle of evil and sin. And so, instead of being born in a palace to people with power, Jesus was born to a poor couple in the midst of the chaos and upheaval created by the Emperor’s census and then became a refugee, fleeing the darkness to Egypt, of all places.

Why?

Consider the names that the angel revealed to Joseph before Jesus was born. Joseph was understandably upset when he found out Mary was pregnant. He was prepared to quietly divorce her. But then the Lord spoke.

“Joseph, son of David, do not fear to take Mary as your wife, for that which is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” (Matthew 1:20-21)

And Matthew comments on this, saying:

All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet:

“Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son,

and they shall call his name Immanuel”

(which means, God with us). (Matthew 1:22-23)

You shall call his name Jesus. “Jesus was a common name. It’s a variant of “Joshua” and it means “Yahweh Saves”. And it was a common name precisely because of the darkness in which the people lived. They were desperate for the Lord to save them and we know that especially in the time in which Jesus was born the people were particularly expectant—the worse things got, the stronger their hopes became—and things were horrible. And so, as Joshua led God’s people into the promised land, Jesus was sent to lead his people in a new and bigger and better exodus into a new and bigger and better promised land. In the first exodus the Israelites became a nation and were delivered from the bondage of Egypt; in this new exodus all humanity is to join in Jesus as the new Israel and in him the Lord will save them—save us—from our bondage to sin and death.

And yet it’s in Matthew’s commentary that we see the “how” of it all. This he says is to fulfil what Isaiah spoke: “The virgin shall conceive and bear a son and he shall be called Immanuel, which means ‘God with us’.” I talked about this last week, but let’s look at it briefly again. Matthew quotes from Isaiah 7:14. No one before Matthew ever seems to have understood this passage as pointing to the future Messiah. Isaiah had spoken these words over seven centuries earlier and he spoke them to King Ahaz of Judah during another very dark time for the Lord’s people. The king of the northern tribes of Israel had made an alliance with the king of Syria and they laid siege to Jerusalem. King Ahaz and his people were scared, but through the prophet the Lord exhorted them to stand firm in faith. They were to trust him and he would vanquish their enemies and this promised child was a sign. A young woman, perhaps Ahaz’s wife or daughter or Isaiah’s own wife, would bear a son and before he’s old enough to know the difference between good and evil the Lord would make good on his promise to deliver his people. The child was to be prophetically called “Immanuel—God with us”, giving assurance to the people that the Lord had heard their cries from the darkness, that he would visit them, and that he would deliver them.

Just as the exodus in the days of Moses became an image of the ministry of Jesus leading his people out of sin’s bondage, the baby—Immanuel—born in the reign of Ahaz became another image of Jesus’ ministry. In him God once again had heard the cries of his people from the darkness—the darkness of Herod, the darkness of Caesar—in Jesus he visited his people, and in Jesus he delivered them. Even more so, Jesus is literally “God with us”. In him God took on our human flesh, becoming one with us. He was born not in some privileged palace to wealthy or noble parents, but to a humble couple just as they were being submitted to the indignity of Roman rule. Almost immediately he was made a refugee by the wicked and murderous King Herod. In Jesus, God is truly with us in every way imaginable, sharing our nature, sharing our life, sharing our pain, sharing our griefs, sharing our humanity—sharing our everything. Jesus has come into the darkness and into the pain and into the grief. This is how the Lord saves.

Joseph and Mary’s flight to Egypt underscores just how Jesus came into the midst of the darkness and not just that he’s come and joined us in it, but that he’s found us in the darkness and so that he can lead us out. After telling us about the angel warning Joseph to flee to Egypt, Matthew tells us that this took place to fulfil what the prophet Hosea wrote: “Out of Egypt I called my son.” But Hosea wasn’t looking forward to the Messiah—to Jesus—when he wrote those words. He was talking about Israel. She was the Lord’s son and the Lord called that son and rescued that son out of Egypt. And now Jesus is constituting a new Israel where the old Israel had failed. He is the Lord’s Son and the Lord will call him from Egypt as he once did Israel. Matthew points to Jesus as the fulfilment and the culmination of Israel’s story.

And then as Matthew writes about the slaughter of the children of Bethlehem, he quotes from Jeremiah’s prophecy:

“A voice was heard in Ramah,

weeping and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be comforted, because they are no more.” (Matthew 2:18)

It might seem like an odd passage to quote. When Jeremiah wrote those words he was writing to the people of Judah during their exile in Babylon. It’s a passage, first, of mourning. The children of Rachel had lost everything. Think of the darkness of the world. Israel had lost it all: her land, her prosperity, her temple. Everything that the Lord had promised and everything that reminded them of their status as the Lord’s people had been taken away. Had the Lord forgotten them? That was what they asked as they wept by the river of Babylon. But Jeremiah then wrote about the Lord renewing his covenant with Israel. When she had repented he would restore her to the land he had promised and he would make her prosperous again. Eventually the Lord did restore Israel. She returned from exile. She rebuilt Jerusalem and rebuilt the temple. But the darkness remained. And so Matthew recalls the time of the exile, of Israel in mourning, and he does so to say that in Jesus, the Lord is acting once again to rescue his people from the darkness, from their exile, and to restore and renew his covenant with them.

And, finally, at the end of today’s Gospel we’re told that when the family returned from Egypt and heard that Archelaus was in power, Joseph decided to settle the family in Nazareth—about as far from Archelaus as he could get. And Matthew says in verse, 23, that this was “so that what was spoken by the prophets might be fulfilled, that he would be called a Nazarene.”

Again, Matthew doesn’t use or quote the prophets the way we might expect him to, as if there’s a one-to-one equation between Isaiah or Jeremiah and the events surrounding Jesus’ birth. Verse 23 continues to raise questions after two thousand years, because there is no mention of Nazareth anywhere in the Old Testament. None of the prophets says anything about Jesus being a Nazarene. The most likely explanation is that Matthew was making a word play. In Isaiah 11:1 the prophet wrote about the Messiah:

There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse,

and a branch from his roots shall bear fruit.

They key word is the word “branch”. In Hebrew the word is nazir, which sounds like Nazareth or Nazarene. It’s not the sort of thing we would do with an Old Testament text, but it’s just the sort of sounds-like word game that was common then. The point is that Jesus has a royal lineage. The Lord had established a covenant with David that his house would be established forever. In the course of history, David’s house eventually fell. No descendant of David ever returned to the throne after the exile, but the covenant was still there. A shoot from the cut-off and seemingly dead stump of Jesse—David’s father—would one day come forth and that branch—that nazir—would bear fruit.

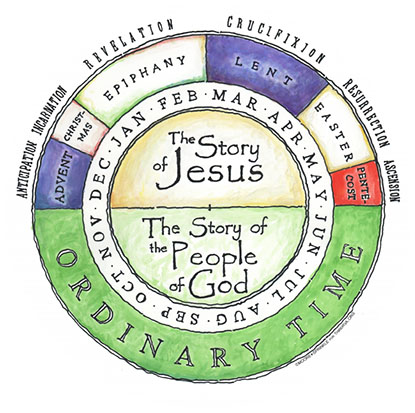

Do you see what Matthew is doing here? Think of the big picture—the sweep of Israel’s story as it’s told in the Bible. That’s what Matthew is getting at with these quotes from and references to the prophets. Matthew’s putting the great themes of the story of God and Israel in front of us and showing how, in Jesus, the story is reaching its climax. Quoting Hosea he reminds us of the Exodus. Quoting Isaiah 11—the passage about the branch or nazir from Jesse—he reminds us of the covenant the Lord established with David. And quoting Jeremiah 31 he gives a vivid picture of Israel’s need for rescue and of the darkness in which the world was lost. Again, Jesus didn’t parachute into history at random. Matthew stresses that Jesus came when the time was exactly right and that he came as the culmination of Israel’s story. In him all the covenants and promises the Lord had made to Israel are brought together and fulfilled. Jesus is Israel, which is why St. Paul can talk about gentiles like us being grafted into Israel. John the Baptists warned, as he preached the need for repentance in preparation for Jesus’ coming, that the Lord would lay his axe to the dead wood of Israel while raising children for Abraham from the stones.

Brothers and Sisters, this means that by faith in Jesus, you and I are now part of this story—the story that goes back to God’s covenant with Abraham, to the Exodus from Egypt, and to the covenant with David. All those who are in Jesus the Messiah—all those who have turned aside from everything that is not Jesus and instead have laid hold of him in hoping faith with both hands—share in the great story of Israel and of Israel’s God and in his promise to deliver us from the darkness, to deliver us from our bondage to sin and death. As Jesus came to bring light into the darkness—into the darkness of Caesar’s empire and of Herod’s brutal and murderous cruelty, Jesus has come to bring light into our darkness.

Listen to the words of our lesson from Isaiah 61:1-3. These were the words Jesus preached from in the synagogue in Nazareth at the beginning of his ministry and they were words he claimed for himself. This is what he came to do. This is how he came to be light in the darkness.

The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me,

because the Lord has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor;

he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and the opening of the prison to those who are bound;

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor,

and the day of vengeance of our God;

to comfort all who mourn;

to grant to those who mourn in Zion—

to give them a beautiful headdress instead of ashes,

the oil of gladness instead of mourning,

the garment of praise instead of a faint spirit;

that they may be called oaks of righteousness,

the planting of the Lord, that he may be glorified.

This is Jesus—the Lord’s salvation. This is what it looks like for God to be with us. He has delivered us from bondage to sin and from the fear of death, its wages. There’s darkness all around. Again, all we have to do is turn on the evening news, read the paper, or look on the Internet. As we gather here today, the world appears to be on the brink of yet another war. But even if that weren’t dominating the news, we all have our own struggles much closer to home. We struggle with our own sins. We struggle with our own strained and broken relationships. We struggle to make ends meet. We struggle through pain and sickness and death. Brothers and Sisters, Jesus has come into the darkness. He has shared it with us. He knows and he understands. And so Jesus speaks good news to us, he binds up our broken hearts. He takes away the ashes that have been poured on our heads and the sackcloth we’ve been wearing in mourning and gives us beautiful headdresses and garments of praise. He is light in our darkness. He is God with us. Isaiah says that this is so that we will be called “oaks of righteousness” planted by the Lord so that he will be glorified.

Having God with us brings amazing transformation. Imagine the chaos of the world all around, lost in sin, everyone struggling to get on top. Think of our own suffering and pain and grief. And then picture what we become when God is with us. Isaiah says we are oaks of righteousness. Look at those huge oak trees outside the windows. They’ve been here forever. As our building deteriorated in the 50s, 60s, and 70s those trees only got stronger and bigger. The storms come and go. Every once in a while one of those big storms damages the church building, but the trees are there as strong as ever. They’re an illustration of what Jesus has called us to be: light in the darkness, oaks in the storm, standing firm, making him known, providing a place of shelter to any who will come, giving a foretaste of his glorious kingdom and inspiring everyone around us to give glory to God. He has not abandoned us. In Jesus he saves. In Jesus he has come to be with us—to find us in the dark and to make us light.

Let us pray: Almighty God, you have poured upon us the light of your Incarnate Word. Jesus has come. Your light has found us and is with us. Grant us, we pray, that your light be kindled in our hearts and that it shine forth in our lives that the world might see it in us and give you glory, we ask, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.