A Sermon for the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity

A Sermon for the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity

2 Corinthians 3:1-11

by William Klock

Letters of recommendation were a big deal in the ancient world. If someone showed up claiming to be someone or something, they often carried letters of recommendation to prove it. You couldn’t just look someone up on the Internet back then. And it wasn’t just important in the secular world, it was in the Church, too. A document from the late First Century called the Didache or “Teaching of the Twelve Apostles” describes churches writing letters of recommendation for people so that when they went from one church to another claiming to be teachers and servants of Jesus the people in the new church kne these folks were legit. This is the background of this morning’s Epistle from 2 Corinthians. In 3:1 Paul writes:

Are we beginning to commend ourselves again? Or do we need, as some do, letters of recommendation to you, or from you?

Paul had a difficult relationship with the Corinthians. Even though he’d started the church and had spent a lot of time with them, the Corinthians didn’t have much respect for Paul. The Christians in Corinth, in particular, were especially prone to getting carried away with the values of their Greco-Roman culture. Greeks placed very high value on a certain kind of rhetorical skill. They valued people who were good speakers and fast thinkers and from what we can gather, Paul may not have shone in those areas the way some other teachers did. The parallel in our culture might be the value we place on flashy production values and preachers and churches that appeal to our egos and felt needs. Paul’s would be the preacher who sometimes stumbles over his words, isn’t handsome, and wears a shabby suit and if the Corinthians were modern North Americans they’d be passing him over in favour of the slick, handsome, prosperity huckster in his expensive suit and whose services seem more like rock concerts. Paul didn’t meet their expectations and so when he heard about their problems and wrote to them giving advice, they wrote back and told him “Thanks, but no thanks. We’d rather take advice from So-and-so.

Reading between the lines, it seems that they’ve told Paul that if he wants to come back to Corinth he’ll need a recommendation from someone they respect. And at this point we might think Paul would have been in the right to shake the dust off his shoes and forget about these ingrates in Corinth. After all, this whole recommendation thing was pretty much the opposite of what Paul was all about. The gospel commends itself and so does a real gospel preacher. And so look at how Paul responds to them in light of that. If you want to see what grace looks like, here it is. He writes to them:

You yourselves are our letter…

They rejected him. They’ve told him not to come around and not to write to them anymore to give advice. They’ve disrespected and insulted him. And Paul writes: I don’t need a letter of recommendation to prove my credentials as an apostle and servant of Jesus. No. You people yourselves are my letter of recommendation. You people, even though you’ve rejected me, you’re the proof of my credentials.

You yourselves are our letter, written on our hearts, to be known and read by all; and you show that you are a letter of Christ, prepared by us, written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts.

If that’s not grace I don’t know what is. Paul doesn’t need a letter written in ink on paper. These messed up, confused, infuriating people are still loved by Paul, because despite being muddled and confused, they’re filled with the joy of the Lord and the hope of his kingdom. For all their faults and for all their inability to see how they’ve been shaped by their culture in their rejection of him, their joy in the Lord and their hope in the Good News is the result of Paul’s ministry to them and that says everything about Paul that needs to be said. Despite their imperfections, they’re his credentials.

When you think about, what Paul writes to them is pretty amazing and it says something about the power of the gospel and Paul’s expectation of its power to transform people, even when they looked hopeless. These were people he rebuked for putting the wisdom of the Greeks over the truth of the gospel. These were people he rebuked for tolerating a church member who was sleeping with his step-mother. These were people he rebuked for dragging each other through the courts, for divorce, for not treating each other as equals, for abusing spiritual gifts, for abusing the Lord’s Supper, for having crazy, disordered worship. The list is a long one. And yet despite their multitude of failings, he says, “You want to see my credentials as a gospel minister, as an apostle? You’re it.” Paul could see the gospel at work in them. As he had written to them in his first epistle, no one affirms that Jesus is Lord apart from the transforming work of the Spirit. Paul could see through the flaws and knew that they believed, that they loved Jesus, that they were full of the Spirit. He had proclaimed the good news about Jesus to them and it had done its work, it was continuing to do its work, and he was confident, it would in time complete its work. This is important. Sometimes we look at other Christians or other churches and they’re a total mess and we’re tempted to write them off completely. Brothers and Sisters, stop. Is Jesus being proclaimed as Lord? If he is, that means that the gospel and the Spirit are at work there. Maybe the gospel and the Spirit have a lot of work yet to do. They needed a correction—a lot of it. But don’t write those folks off. They’ve got the gospel. These aren’t the other folks Paul warns about who preaching another, a different gospel. That’s a whole other problem. No, they’ve received the gospel and the gospel is a powerful thing. It’s the power of God to save.

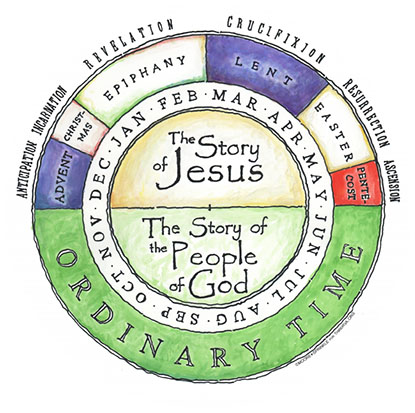

Now, to make his point Paul takes the Corinthians back to the idea of “covenant”. Covenant is critical to who we are in Jesus, but it’s something we often forget. We’ve been shaped more than a little by our own culture’s way of thinking. For about the last century we’ve largely exchanged the biblical language of “covenant” for the language of “relationship” when we talk about how we relate to God. Describing our relation to God in terms of “relationship” or talking about Jesus as our “personal Saviour” isn’t necessarily wrong, but it’s not the language of the Bible and it doesn’t carry anywhere near the depth or the significance of the biblical language and it often tends to miss the bigger picture. The Bible never speaks of “relationship”—that’s squishy modern language; it’s also very individualistic language. God himself, speaks in the Bible of covenant and adoption. There’s more to salvation than me and Jesus. God works with families, with peoples—this is why we baptise our infants as we did Luke this morning. The Church, like Old Testament Israel, is a covenant family. And that’s what Paul goes back to: this idea of being in covenant with God. We aren’t just in a “relationship” with him. We’re his people. We’re his sons and daughters. And we’re in it together—all of us—as the Church, the Body of Christ with all its many parts and members.

Paul takes the Corinthians back to Jeremiah 31. Israel was in exile at that time. God had judged her and allowed the Babylonians to conquer her, to destroy Jerusalem, to tear the temple down to the ground, and to carry the people off into captivity, away from the land they’d been promised. His judgement came on Israel because she was in covenant with him and had failed and refused to live up to that covenant. Relationship may or may not involve responsibility and commitment, but at the core of the idea of covenant are the ideas of mutual commitment and responsibility. Israel had failed to live according to the law the Lord had given her, she’d refused to trust in his goodness and his care, she’d worshipped foreign pagan gods, she’d failed to obey him. Ultimately, she had failed to love him as he loved her and she was unrepentant in her rejection of him.

Through the prophet Jeremiah, the Lord promised the people that he would redeem them. They may be covenant-breakers—like a cheating spouse—but he was not. And so one day he would restore Israel by establishing a new covenant. There would be a new agreement between the Lord and his people. There would be a new marriage between Israel and her Lord. He had established the old covenant through Moses when he gave Israel his law, written on stone tablets. But that law carved on stone did not have the power to give the people the real life they needed and that the Lord desired for them. And so the Lord promised a new covenant that would restore Israel. The new covenant would deal with the sins of the people—that’s what the Cross of Jesus is about. And the new covenant would give the people the new life they needed to truly be the renewed people the Lord wanted them to be—to remake humanity into what we were meant to be—God giving his people his own life, transforming their hearts and minds in a way that the law written on stone was never able to do. In this new covenant, the Lord promised through Jeremiah, he would carve the law on their hearts—he would give his people his own Spirit.

And despite how muddled and confused and wrong the Corinthians were on so many things, despite their rejection of Paul, he could write to them and say that they were his letter, they were his credentials, because the life of the Holy Spirit was evident in their life as a church. They themselves are a letter from Jesus the Messiah. The powerful work promised through Jeremiah and the other prophets is manifest in the amazing work that the Spirit has accomplished in them. Think about that. Some of them had been Jews—the same sort of Jews that Paul himself had been when he persecuted Jesus’ people. Some of them had been Greek pagans, worshipping Aphrodite with ritual prostitution and some had been sold out to Caesar who claimed to be the divine saviour of the world. But Paul had brought them the good news that Jesus is Lord. He preached Jesus’ death and resurrection. And they had been transformed. The Spirit had moved them to repentance and given them a totally new life. The living God had written something powerful on their hearts and they would never be the same people again. And the pagan world around them could see it even if these people couldn’t see it themselves anymore. Again, think about that. Think about your own stories. Think of the way you were once met with the Good News. Think of the forgiveness you have found at the Cross. Think of the new life Jesus has given you. Just like the Corinthians, each of us has a long road ahead of us as we grow into a mature faithfulness to Jesus and his lordship, but Jesus has poured his Spirit into us. In our baptism he has plunged us into the Holy Spirit and we are not the people we once were.

And so Paul goes on, getting back to his credentials, writing in verses 4-6:

Such is the confidence that we have through Christ toward God. Not that we are competent of ourselves to claim anything as coming from us; our competence is from God, who has made us competent to be ministers of a new covenant, not of letter but of spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.

All the proof of Paul’s faithfulness as a minister of the Gospel, as a minister of God’s new covenant is right there in the work accomplished in the Corinthians by Jesus and the Spirit. It’s not that Paul is competent himself. He merely showed up in Corinth and preached the Word as he’d been called to do by Jesus himself. But as a result of Paul preaching the Good News of Jesus and the kingdom the new covenant has unfolded right there in a powerful and very visible way. The “letter”—the old law written on stone—brought death, but the Spirit now poured into them has given them life. In his resurrection Jesus unleashed life into the world. All Paul has done is preach that Good News and where he’s done that the Spirit has brought transformation.

At this point Paul changes tack a bit. The reason the Corinthians rejected him and the reason he’s had to explain all this about the new covenant to them is that they’ve lost sight of what’s important. Again, they’d been captivated by teachers who met superficial criteria of Greek culture as to what a wise teacher was supposed to be like. Again, the parallel today would be the way people are attracted to programs and high production values and slick talkers in faddish clothes or slick suits who pander to the consumerism, the materialism, the individualism of our culture. And so in verse 7 and 8 Paul starts trying to stress the glory of the new covenant that the Corinthians seem to have forgotten.

Now if the ministry of death, chiseled in letters on stone tablets, came in glory so that the people of Israel could not gaze at Moses’ face because of the glory of his face, a glory now set aside, how much more will the ministry of the Spirit come in glory?

Paul takes them back to the Exodus as he does so often. They all knew the story. For those who were Jews this was part of their national and cultural identity. In Exodus 34 we read how the Israelites became afraid after Moses had been up on Mt. Sinai for a long time. They saw the thunder and lightning and they thought God was angry. Ironically, Moses was up on the mountain being given instructions on how the tabernacle was to be built, how all the furnishing and vestments were to made, and how the people were to worship the Lord. But down at the base of the mountain the people were convincing Aaron, Moses’ brother, to take their gold and make them an idol in the shape of a calf. Here they were on their honeymoon, prostituting themselves to an idol. Moses came down from the mountain and the first words he was given by the Lord to speak to the people amounted to a death sentence for their idolatry. Moses pleaded with the Lord to spare the people despite their guilt and as a result of his pleading prayer the Lord revealed his nature and character even further. Even though the Lord insisted that Israel’s wickedness had to be addressed and dealt with, he was still a god of abundant mercy. As a result of that revelation, Moses went down the mountain and his face was shining. The radiance of the Lord, reflected from Moses’ face was so great that the Israelites were afraid—they knew their sin and cowered in the presence of the holy, even though it was only the reflection of the Lord’s holiness. Moses had to veil his face. The only time he unveiled it was when he went into the Lord’s presence in the Tabernacle, to speak with him face to face. Now, Scripture doesn’t explain the mechanics of it. I know I can’t quite picture how Moses’ face radiated the glory of God, but somehow it did. And it was absolutely magnificent and utterly overwhelming.

And Paul’s point is this: If the law carved on stone came down from the mountain in such amazing glory, and if the judgement of the Lord on Israel’s idolatry was manifested in such glory, how much more glorious is ministry of the Spirit? He goes on in verses 9-11:

For if there was glory in the ministry of condemnation, much more does the ministry of justification abound in glory! Indeed, what once had glory has lost its glory because of the greater glory; for if what was set aside came through glory, much more has the permanent come in glory!

Like the Christians of Ephesus who, in Revelation, are described as having lost their first love, the Corinthians had lost sight of the glory of the Holy Spirit’s ministry. It wasn’t that they’d lost the Holy Spirit. That’s impossible. It’s the Spirit who binds us to Jesus, he’s the one who unites us to his life, he’s the one who renews our minds and regenerates our hearts, turning us from everything that is not Jesus and giving us the desire and the faith to take hold of Jesus with both hands. You cannot be a Christian without the Holy Spirit. But somehow they’d lost perspective. The Spirit had empowered them remarkably, they had no shortage of gifts, but they’d lost sight of the gospel, Jesus was no longer their centre, and they misused and abused those gifts. And they let the values of Greek culture displace a gospel-centred life.

Brothers and Sisters, we can all too easily fall prey to the same sorts of things. Our own culture infiltrates the church in many, many ways. Our culture is overwhelmingly commercialistic, materialistic, and individualistic and too often, without even realizing it’s happened, we start building our churches around these things. We treat the gospel like a commodity to sell. We displace it with programs and we tailor our preaching to appeal to our culture’s self-centred individualism. Programs can be good and useful in accomplishing the work of the Church, but most of the time these days they’re seen as sales tools. But God doesn’t give us programs. He gives us his Word. Through the ministry of the Spirit he caused his Word to be written by prophets, apostles, and evangelists so that we can know him and proclaim him to the world. And in Jesus he sent his Word to become flesh—not to give us programs or gimmicks or to tickle the itching ears of sinners—but to die for our sins and to rise again to unleash life into the world. A Church should never have its identity tied up with anything other than the gospel. A Church is a place where the Word is faithfully preached and the Sacraments faithfully administered. That was the definition the Protestant Reformers developed. What constitutes a Church? A Church is a body that preaches the Word and administers the Sacraments. But today it seems many preach everything but the Word and the Sacraments are often side-lined or even sometimes considered optional. As ministers of the Gospel, we—and that’s both you and I—are not called to be flashy, we’re not called to preach the pop-psychology and self-help that our culture obsesses over, we’re not called to be motivational speakers, we’re not called to preach health and wealth even though that’s what people want to hear—we’re called to proclaim that Jesus has died and risen and that he is Lord. And we’re called to back-up that proclamation by living the life of the Spirit, by manifesting the love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, gentleness, and self-control that the Spirit bears in our lives. We’re called to live justly and to do mercy. We’re called to use the giftings of the Spirit not for our own ends, but for the sake of the gospel and for the well-being of the Church. We’re called to be gloriously counter-cultural: being poor in spirit, mourning sin, living in meekness, hungering and thirsting for righteousness, being merciful, and making peace—even when it means rejection and persecution. Brothers and Sisters, it’s this Jesus-centred and Spirit-empowered life that manifests the glory of God to the world, that makes us the light of the world and the salt of the earth—the marks us out as the covenant people of God.

Let us pray: Heavenly Father, we thank you this morning for the forgiveness and new life you’ve given us through the death and resurrection of Jesus. We thank you for pouring your Spirit into us, uniting us to Jesus and transforming us. In us you’ve revealed your glory. We ask that you would, in your grace, keep us from taking the life of the Holy Spirit for granted and that you would keep us focused on your priorities despite the competing priorities that surround us in the world. Keep us faithful to Jesus, to his kingdom, to your Word and to your Sacraments, and to preaching the Good News that Jesus has died and risen and is Creation’s true Lord. We ask all of this through him. Amen.