A Sermon for Passion Sunday

A Sermon for the Fifth Sunday in Lent

Hebrews 9:11-15 & St. John 8:46-57

by William Klock

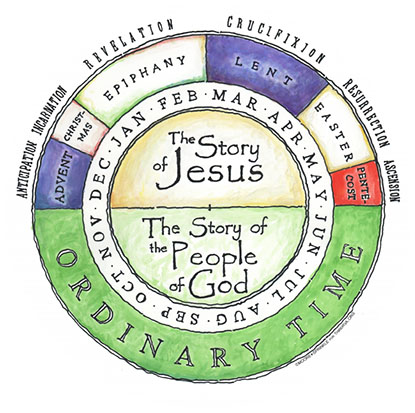

Today, the Fifth Sunday in Lent we enter a sort of “sub-season” within the larger season of Lent. Historically the Church called it “Passiontide”. During Holy Week, beginning with Palm Sunday, we recount the passion of Jesus as we prepare for Easter and the celebration of his resurrection. But today the lessons prepare us for. Whenever the Church gives us a major feast day, it often gives us a Sunday that explains why the events that feast commemorates are important. Usually it’s after the feast day, but for Palm Sunday and Holy Week the explanation comes first. That’s what our lessons are about today—they tell us the theological and the narrative importance of Jesus’ suffering and death.

Some of you know that this year I’ve been working on a project, writing some commentary on the Epistles and Gospels, to help fellow preachers to think through them from what’s called a narrative-historical perspective—basically to preach on the Scripture lessons as parts of the big story of God and his people. As part of that project I’ve also been doing historical study on how the lessons each week were selected and why. A lot of interesting and helpful stuff can come out of that. This week the old Latin name for this Sunday struck me. Before it was called Passion Sunday, it was known as Iudica. I’d seen this in some older Lutheran commentaries—until the 70s they often used the old Latin names—but I’d never given it much thought. I discovered this week that it comes from the old introit—Anglicans stopped using those in the 1550s—but the old introit was from Psalm 43:

Give sentence with me, O God, and defend my cause against the ungodly people:

O deliver me from the deceitful and wicked man, for thou art the God of my strength.

The Psalmist pleads with God: Give sentence with me. In Latin it’s Iudica me. Judge me—or more appropriately, vindicate me. It was once the prayer of the Psalmist against his enemies but it now becomes the prayer of Jesus as he faces the final rejection of his own people and goes to the cross. So far in the Lenten Gospels we have walked with Jesus as he made his final trip to Jerusalem. Now, in today’s Gospel, St. John recounts one of his final disputes with the Jews. The lesson picks up the theme of last Sunday’s Epistle as Jesus makes clear what it means to be the children of Abraham and inheritors of the Lord’s promise to him. The passage ends with an attempt by the Jews to stone him, foreshadowing the Palm Sunday Gospel and the events of Holy Week. The Epistle prepares us theologically for Jesus’ Passion as it holds him up, our high priest, as the fulfilment of the old covenant and its promises. And this cry that has become today’s theme, “Vindicate me, O God” runs all through the lessons.

It's probably most obvious in the Gospel. Look at John 8, beginning at verse 46:

Which one of you convicts me of sin? If I tell the truth, why do you not believe me? Whoever is of God hears the words of God. The reason why you do not hear them is that you are not of God.”

The Jews answered him, “Are we not right in saying that you are a Samaritan and have a demon?” Jesus answered, “I do not have a demon, but I honor my Father, and you dishonor me. Yet I do not seek my own glory; there is One who seeks it, and he is the judge. Truly, truly, I say to you, if anyone keeps my word, he will never see death.”

Why would the people accuse Jesus of being a Samaritan and of having a demon? It helps to backup a bit. Our Gospel today is taken from the middle of a longer confrontation between Jesus and the Jews. Some hear his words and believe, but others continue to oppose him and we can hear the voices getting louder and angrier as we make our way through the chapter. The chapter ends with Jesus narrowly escaping an attempted stoning. The conversation has involved talk of Abraham and of who his true descendants are—are they those carrying Abraham’s genes or are they those who have acknowledged that Jesus is the Messiah and are following him? In verses 37 and 38 Jesus acknowledges that the Jews are Abraham’s children by birth, but hints that their true father might be someone else, seeing that in opposing Jesus, they’ve rejected the Father and the covenant he established with Abraham. They protest, but Jesus continues, shifting from Abraham to God, ““If God were your Father, you would love me, for I came from God” (v. 42). The devil is a murderer, Jesus says, and your murderous rage aimed at me shows who your real “father” is. You’re children of the devil and this is why you refuse to listen to me.

Now we see how these folks throw the accusation back at him. They’ve already hinted at the issue of his parentage (which strongly suggests that the unique situation of Mary’s pregnancy was public knowledge) and now they accuse him of being a Samaritan (a cheap shot, accusing him of not being a real Jew), and of having a demon. “No, I don’t have a demon,” Jesus responds, “but, at any rate, call me what you will. I’m not out for my own glory. I’m here to glorify the Father and he will be my judge, not you.” And Jesus goes on pleading with them. The message of the Father is one of deliverance: “If anyone keeps my word, he will never see death.”

One might think that the Pharisees would have an “Ah-ha!” moment here, but just the opposite happens:

The Jews said to him, “Now we know that you have a demon! Abraham died, as did the prophets, yet you say, ‘If anyone keeps my word, he will never taste death.’ Are you greater than our father Abraham, who died? And the prophets died! Who do you make yourself out to be?” Jesus answered, “If I glorify myself, my glory is nothing. It is my Father who glorifies me, of whom you say, ‘He is our God.’ But you have not known him. I know him. If I were to say that I do not know him, I would be a liar like you, but I do know him and I keep his word. Your father Abraham rejoiced that he would see my day. He saw it and was glad.” So the Jews said to him, “You are not yet fifty years old, and have you seen Abraham?” Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I am.” So they picked up stones to throw at him, but Jesus hid himself and went out of the temple.

The irony is that the Pharisees were actually staunch believers that one day God would resurrect the dead to life, but they’re so furious with Jesus that they miss his point. No, they see this as clinching proof that Jesus really is possessed by a demon. It’s the only explanation for his crazy-talk. Abraham died. The Prophets died. If they were the greatest in Israel and they died, who does Jesus think he is making such claims about never dying? Yes, they believed that God would one day raise the faithful in Israel, but that vindication of the faithful hinged, they thought, on faithfulness to torah. What’s got them so worked up is that Jesus is now saying that God’s future vindication of his people will hinge not on faithfulness to torah, but on faithfulness of Jesus. That’s not to say that there’s anything wrong with torah, but that it’s not the defining mark of the people of God that they think it is. Jesus points back to Abraham to make his point. Abraham’s hope wasn’t in torah. It couldn’t have been. He lived hundreds of years before it was ever given, but he hoped in the promises of God anyway. Abraham looked forward in hope to the day when the Lord’s promises would be fulfilled and Jesus is saying: “That day has now come and it’s happening through me.” This is the point of that line, cryptic to us, but that was ever so clear to those angry Pharisees: “Before Abraham was, I am.” Jesus identifies himself with the promises of God—with God’s word. “I am” is the meaning behind the divine name, Yahweh. John must have had this in mind when he penned the words of his prologue, “The word become flesh”. This is why Jesus can claim not only such a close association with the Father, but that to obey and follow him as Messiah is the criteria for inheriting the promises of God and, therefore, of being his true people, his true Israel.

The iudica theme of the day, the call for God’s vindication, runs like a thread through the Gospel. Already, the Jews are issuing a false judgement against Jesus, foreshadowing the events of Passiontide. But Jesus points them to the Father. He is the only judge who matters. He will vindicate his son and overturn the false verdict of the Jews. And this is how the Lord’s deliverance will come to Israel. As the Father vindicates Jesus and raises him to life, so he will vindicate the people who keep Jesus’ word (to use the language of verse 52). As death has no hold over him, neither will death have a hold over his people.

Now today’s Epistle. The book of Hebrews was written anonymously and debate over who its author may have been is not likely to be settled any time soon. There are good reasons to believe it wasn’t St. Paul, but there are also reasons to think it could have been. The book was written to Jewish believers and explains the good news about Jesus in light of the old covenant. That old covenant was familiar territory and many of the first Jewish Christians struggled to understand it in light of Jesus. After his conversion, Paul spent a good bit of time in solitude, working through these issues and came back having worked these matters out for himself and ready to help the rest of the Church to do the same. In many ways, Hebrews seems to work through what must have been Paul’s thought process or something very much like it.

In any case, the Church puts this selection from Hebrew before us this Sunday so that we will better understand the Passion of Jesus as it unfolds over the next two weeks. Specifically, the writer of Hebrews explains what the death of Jesus has done for his people in light of the sacrifices of the old covenant. Let’s read our text again, Hebrews 9:11-15.

But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. For if the blood of goats and bulls, and the sprinkling of defiled persons with the ashes of a heifer, sanctify for the purification of the flesh, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to serve the living God.

Therefore he is the mediator of a new covenant, so that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance, since a death has occurred that redeems them from the transgressions committed under the first covenant.

The sacrificial system was at the centre of Jewish life under the old covenant and, particularly, the idea of atonement for sins by blood. Of course, the difficulty for many people was that the sacrificial system seemed to work just fine as it was. Yes, you had to make sacrifices repeatedly because sin still happened, but they just accepted that this is how things were and how they always would be and the Lord be praised for providing a means of redemption. Apart from that well-known passage, Isaiah 53:10, which speaks of the sacrificial death of God’s “suffering servant”, no one ever considered that this system might one day be superseded by something better, let alone that this might happen through the self-sacrificial offering of one of the priests, or even by God himself. Jesus seems to be the first person to have come to this conclusion and even his own disciples struggled to grasp it conceptually. And yet once it happened, there it was. But people still struggled to understand it. Jesus walked his friends through the Old Testament scriptures that first Easter as they travelled the Road to Emmaus and they understood. Paul met the risen Jesus and understood as well, although it took working through the implications of accepting that Jesus really was the Messiah for it to become plain as day. But this realisation that the old covenant sacrifices were preparing Israel for Jesus and for the cross is one of those things that once you see it, you just can’t unsee it. Hebrews was written so that all God’s people would finally see it for good.

Perhaps the difficulty began with the Jewish understanding of the tabernacle and later the temple. The tabernacle was the greatest place on earth, because it was the one place on earth that wasn’t simply “earth”. The tabernacle was the one place where earth and heaven intersected, where human beings could go to encounter the presence of God. How could anything top that? And yet the writer of Hebrews tells us, going back to Chapter 8, that the tabernacle was really only a temporary stand-in for the heavenly sanctuary, for the actual dwelling of God, so holy no human could ever approach. But we can draw near, as the Israelites discovered, through the work of priestly mediators who entered first bearing the sacrifices of the people. Similarly, it was difficult for Jewish people to comprehend a better sacrifice, but that’s just what Hebrews tells us Jesus is. He entered, not into the earthly tabernacle, but into the heavenly—directly into the presence of God—and he went in on our behalf, not bearing the blood of bulls or goats, but bearing his own blood.

Even if no one saw it coming, the old covenant was preparing God’s people for all of this. We see this preparatory role in the old covenant sacrifices as well. The sacrifices taught God’s people that sin and redemption from it are serious business. It costs the sacrifice of something valuable. The blood poured out from those animals reminded the people that the “wages of sin is death”, but that God mercifully accepts the death of another on our behalf. That the Lord ordained the sacrificial system was also a powerful reminder that God desires his people to live in his presence and wants us to be forgiven, cleansed, and made holy. Again, no one saw it coming, but once Jesus had died and been raised from death, it became impossible not to see that those sacrifices were preparing Gods’ people for Jesus. He took up Israel’s role and identity himself and offered himself as a once-for-all and perfect sacrifice for their sins filling the role of both priest and victim.

Finally, Jesus and the old covenant are contrasted in terms of the efficacy of the sacrifice. The old covenant sacrifices purified the flesh, but the underlying problem of the sinful heart remained. This simple predicament should have had Israel looking for a better sacrifice from the beginning, but again, it actually took that better sacrifice taking place before anyone understood. Throughout her story, the faithful of Israel lamented the nation’s predicament. No amount of sacrifices ever set Israel’s heart right. The people longed for the day that the prophets foretold, a day when the Lord would pour out his Spirit to set the hearts of Israel right once and for all. In Jesus it finally happened: a perfect sacrifice that purifies not only the flesh, but that also purifies the hearts of his people and makes them holy. Our passage here speaks of Jesus offering himself a sacrifice “through the eternal Spirit”—likely a reference to Isaiah 42:1 and to the anointing of the Spirit that took place at Jesus’ baptism—but it is difficult to read of Jesus’ Spirit-empowered ministry and not see the way in which, through him, the same Spirit has been poured into the hearts of his people. In this way, Jesus has purified our consciences—purified us where it really matters so as to transform our affections—that we might set aside “dead works” to serve the living God.

“Dead works” likely refers to those old covenant sacrifices and purity codes that, while good and God-given, could never fully deal with the problem of sin and death. The phrase may also include the old pagan practises of gentile converts, although the emphasis is clearly on the sacrificial system of the old covenant. The point isn’t that the old covenant was bad. It was astoundingly good. Those “dead works” maintained Israel’s communion with the Lord. The point here is to contrast the old and the new. A few years ago when I preached on this passage, I had two of my lanterns with me: an old one my family used to use that I had always thought was plenty bright, and another more recent one that is retina-scorthingly bright. The old was good, but it now seems so dim in light of the newer, brighter one. So the writer here uses “dead works” to contrast with “living God”. In Jesus, God’s people have finally been freed from the bondage of sin and death to live in the presence of God and as stewards of his life. Our vocation is the vocation that God gave to Abraham and his descendants, but now made possible as never before as Jesus and the Spirit have purified us from the inside out.

I want to bring this back to that old introit from Psalm 43. The Psalmist prayed, “Give sentence with me, O God.” Judge me. That’s a dangerous thing for a human being to pray. God judges sin and sinners and we’re sinners and our lives are full of sin. We deserve death. But thanks be to God that by our union with Jesus, we can cry out in faith with the Psalmist: “Judge me.” And we can be sure that through the merits of Jesus our Lord God’s judgement will be our vindication.

Let’s pray:

O Almighty God, Who hast sent Thy Son Jesus Christ to be an High Priest of good things to come, and by His own Blood to enter in once into the holy place, having obtained eternal redemption for us; mercifully look upon Thy people, that by the same Blood of our Saviour, Who through the eternal Spirit offered Himself without spot unto Thee, our consciences may be purged from dead works, to serve Thee, the living God, that we may receive the promise of eternal inheritance, through Jesus Christ our Lord.